EU-LISTCO newsletter with insightful analysis, latest news, and events.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under grant agreement no. 769886

AUGUST 30, 2018 | NEWSLETTER 1

Welcome to EU-LISTCO’s First Newsletter!

It is being published just six months after the launch of this very ambitious and exciting project, whose main task is to delve into the challenges facing European foreign policy.

In this issue

Quick takes: What are the project’s goals? The project team explains

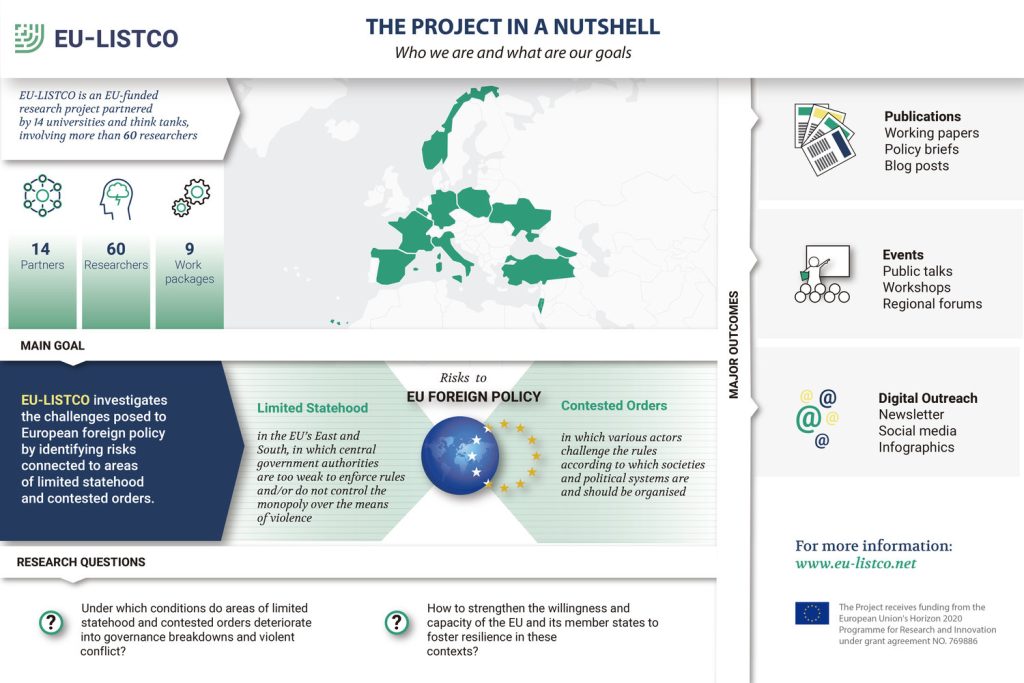

Infographic: EU-LISTCO in a nutshell

Latest publications: Stalemate in the Caucasus

Recent events: EU-LISTCO’s kick-off conference

In the news: Choice readings

INTRODUCING EU-LISTCO

There has been any number of studies, workshops, seminars, and commentaries devoted to European foreign policy. But EU-LISTCO is different for three main reasons. It focuses on areas of limited statehood, where central authorities are too weak to set or enforce decisions. It focuses on contested orders, where external or domestic actors quarrel over the political, economic, or social system. And it brings together a group of fourteen leading research institutions from across Europe and the Middle East which, with their different backgrounds and experiences, aim to assess just how prepared the EU and its member states are in dealing with areas of limited statehood and contested orders. The consortium will also delve into the immensely complex issue of identifying risks for governance breakdown and violent conflict and how Europe can strengthen resilience in its neighbourhoods.

The launch of this project, funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme, couldn’t be more timely. Just consider Europe’s Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods.

Ukraine is struggling to underpin its statehood with strong, independent institutions. All the while, there is the persistent backsliding over tackling corruption. There’s the pressure on curbing accountability and transparency. There’s the obstinate interference of the oligarchs. Each of these issues has dogged Ukraine since its independence from Russia in 1991. But Ukraine cannot afford to fail. It would pose a threat to Europe’s security. It would also lead to serious unpredictability of the already very difficult relations between Moscow and Kiev.

Then there is the Donbas region. Since 2014, it has been subject to extensive and persistent Russian meddling and continues to be contested—not to speak of Crimea, which Russia illegally annexed in early 2014.

Further south, Ukraine’s neighbour Moldova, riven with corruption, does not control the territory of Transnistria, which has been a Russian pawn since the early 1990s. Not far away is Georgia, where Russia occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia ten years ago—yet another case of contested order.

As for Europe’s southern neighbours, they are not in good shape, to say the least. It would be hard to define statehood in today’s Syria. And if and when the war there ends, contested orders—in terms of borders, geostrategic influences, “statelets,” or ethnically carved-out regions—are bound to come into play.

Across Syria’s border, there is enough contested order between Israel and Palestine, with the latter dogged by weak state institutions, corruption, internal divisions, and Israel’s government hardly now even bothering to pay lip service to the language of a two-state solution. Statehood in Jordan is brittle, while in neighbouring Iraq the idea of statehood so much depends on relations between Baghdad and Erbil but also between the Shite and Shia communities.

But don’t think that areas of limited statehood and contested orders are confined to regions outside of Europe.

The EU’s own institutions and governments are being contested by populist movements, by Eurosceptic parties, and by anti-immigration forces that are championing the ideas of Fortress Europe and a Europe that returns to national sovereignty agendas. All three elements challenge the basic assumptions upon which the EU was built after World War II.

So, in terms of EU-LISTCO, the consortium has enough on its hands. Apart from being “mandated” to assess the preparedness and the ability of EU institutions and governments to deal with these issues, the consortium will consider how resilience in Europe’s neighbourhood can be strengthened. Not an easy task.

Resilience is one of those words that have different meanings for different players. The EU, for example, sees resilience in its Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods as part of a long-term strategy to promote stability, or rather stabilization. A great deal of the emphasis is on security and police training—alongside efforts to strengthen the rule of law and introduce good governance. For the EU, the former often takes precedence over the latter. This raises many questions about the ability of some leaders, such as Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad or Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, to remain in power.

EU-LISTCO does not focus on the resilience of autocratic leaders. Rather, we want to know how and under what conditions societies are resilient in areas of limited statehood and contested orders. Are societies capable of preventing governance breakdowns in such areas, and can they avert order contestations from turning into violent conflict? Are societies confident that the infrastructures—water, energy, sanitation, hospitals, schools, transportation, banking systems—can be quickly restored in the event of natural catastrophes or domestic or external conflict? Do they expect that their democratic structures and institutions are resilient enough to withstand cyber attacks, fake news, and pressures on the liberal order?

These are the big issues that EU-LISTCO will be tackling over the next two-and-a-half years. The EU-LISTCO website will become the home for the project’s research results. Carnegie Europe’s Strategic Europe blog will showcase blogs written by project members (see our kick-off piece below). Social media and policy-driven events will provide opportunities for lively debates. Together, they will become a kind of hub for all the consortium’s ideas that will emerge in the coming months.

—Judy Dempsey, Carnegie Europe Foundation

Quick Takes |

||

Want to know more about EU-LISTCO, particularly what the “Work Packages” are all about? Judy Dempsey asked each of the team leaders the same question: In the context of events taking place in Europe and its neighbourhoods, what is the goal of your Work Package (WP)? Here are their answers.

Tanja A. Börzel and Thomas Risse, Freie Universität Berlin (WP1)

Rather than a ring of friends, the EU seems to be surrounded by a ring of fire. Most researchers and many policy advisors assume that limited statehood and order contestations are per se threatening to the EU and its member states. WP1, in contrast, starts from the assumption that weak state institutions and actors challenging the norms, principles, and rules according to which societies and political systems are—or should be—organized are the default in the EU’s Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods. They might pose risks, but are not threatening as such.

Our main goal is to formulate hypotheses on the conditions under which areas of limited statehood and contested orders are likely to transform from risks to threats for European security.

Identifying the tipping points from risks to threats will enable us to understand how we can foster state, societal, and regional resilience in order to prevent violent conflict and governance breakdown in areas of limited statehood and contested orders. WP1 thereby lays the groundwork for formulating policy options for the EU and its member states in their efforts to promote resilience in Europe’s Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods.

WP1 will not carry out original empirical research. Rather, our mode of operation is to develop a common research template for EU-LISTCO’s various case studies and to revisit the conceptual framework in light of the research findings. This requires constant exchanges with the other work packages in order to synthesise the findings of EU-LISTCO and to make the project useful for practitioners in the EU and its member states.

Sarah Bressan and Philipp Rotmann, Global Public Policy Institute (WP2)

Security policy tries to protect Europe from external threats—but what threats to focus on? There are more risks than our security bureaucracies can constantly analyse in-depth, we will never have a complete list, and we’re constantly surprised when underrated risks suddenly become threats. At the same time, political attention and money for preventing or managing threats—with diplomacy, aid, military force, and many other instruments—are limited. And if governments and the EU could better target their efforts to effectively deal with a multitude of possibilities, they could possibly save more lives.

Our work package creates ways to better understand the multitude and interplay of risks and threats. At the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), our colleagues are building algorithms to make better forecasts about the risks of violence. At the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) and Foresight Intelligence in Berlin, we’re developing methods for systematic interaction between experts to overcome some of our natural cognitive biases, such as the human tendency to take our expectations of the future from a linear extrapolation of the past. We try to identify commonly underrated risks and the tipping points at which they might turn into actual threats, and to improve decisionmaking about engaging with these risks and threats in such a way that strategic choices become more effective across a range of different possible futures.

Amichai Magen, Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya (WP3)

The post-Cold War peace dividend is spent. The golden moment of liberal stability that came with it for Europe is now over. From resurgent authoritarianism (China, Iran, Russia) to new cyber and terrorist threats, and from instability caused by uncontrolled migration to accelerating nuclear proliferation—Europe’s regional and global geostrategic environment is one increasingly characterized by uncertainty, volatility, and danger.

To charter the choppy waters ahead it is essential that the EU becomes better at identifying risks before they degenerate into conditions that seriously threaten Europe’s security.

WP3 makes a central contribution to this effort. It will systematically map and analyse global and diffuse risks that have the potential of either threatening EU security directly or tipping areas of limited statehood into destabilising governance-breakdowns and violent conflicts—with deleterious consequences for EU security.

WP3 covers global risks—that is, risks emanating from territories outside of the EU’s immediate geostrategic environment—as well as diffuse risks, which are not located in a defined territory, such as climate change, transnational crime and terrorism, or cyber-coercion.

As recent developments show, the Southern and the Eastern neighbourhoods of Europe as well as the EU itself are highly affected by both types of risks. WP3 will also formulate policy-oriented insights on how to improve EU’s resilience, its preparedness, and preemptive capacities to better tackle high-priority risks and threats.

Agnieszka Legucka, Polish Institute for International Affairs (WP4)

The goal is to pinpoint circumstances and situations which may lead to governance breakdown and violent conflict in the EU’s Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods. The project aims at determining certain patterns which, in certain conditions, turn countries into volatile situations and disintegration. The main factors to be examined include political revisionism and radicalism, governance of the political economy, migration, and demography.

They are related to three types of actors: the central government and other official bodies and institutions; actors below the level of the government or state; and external actors, including international organisations, non-state actors and the like.

By comparing several cases taken from the EU neighbourhood, WP4 will play a crucial role in identifying conditions and tipping points when areas of limited statehood and contested order worsen to the irreversible point of governance collapse or intense war. WP4 will also investigate how societal and political resilience can be fostered in these areas. The aim of this research is also to determine if the conclusions drawn from the research may be applied to regions other than the EU neighbourhood.

Khalil Shikaki, Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (WP4)

The Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PSR)’s goal is to explore the impact of three dynamics on Europe and its neighbourhood.

First, the popular demands for democracy and rule of law in the Arab World. Second, the increased prospects for the collapse of the Palestinian Authority (PA), the breakdown of the post-Oslo order, and the diminishing prospects for the two-state solution. And third, the continued migration of Palestinian Christians.

PSR seeks to identify conditions under which the demand for democracy might lead to greater political and economic unrest, radicalisation, and potentially violence. The collapse of the PA and the Oslo order might lead to greater support for violence among Palestinians and Israelis and radicalisation. The push and pull factors might lead to the disappearance of Palestinian Christians from the Holy Land.

Finally, we seek to explore possible means of strengthening the resilience of the post-Arab Spring Arab regimes as well as the PA so that they can be made more capable to meet the expected challenges.

In this regard, questions that are likely to be addressed include the following: Is there a conflict between the pro-democracy agenda and those that seek to promote stability? If such a conflict exists, which agenda should the EU adopt? Should the EU strengthen the PA regardless of the prospects for peace based on the two-state solution and regardless of authoritarian trends in the Palestinian political system? Should the EU seek to strengthen the Palestinian Christian community and institutions so that they can become more capable to remain steadfast and prosperous in their own country? In this regard, should the EU seek to reduce “pull” factors that make it easier for Palestinian Christians to seek migration?

David Cadier, Sciences Po Centre de Recherches Internationales (WP5)

While other work packages study the nature of the challenges emanating from areas of limited statehood and contested orders, WP5 analyses how the EU and its member states have been responding to these challenges—and how they could do it better.

The export of norms and standards of democratic governance has been at the core of EU foreign policy. This transformative dynamic is increasingly being tested, however. In Europe’s neighbourhoods, central governments find themselves unable to apply or enforce such norms on their whole territory or in all sectors, while in addition these norms are contested in themselves by external powers seeking to promote alternative models by populist parties inside the EU that are putting into question liberal values.

In this context, WP5 investigates how the capacity and willingness of the EU and its member states to prevent areas of limited statehood and contested orders from turning into violent conflict and governance breakdown can be strengthened. It does so by establishing the criteria for optimal policies, by reviewing the instruments at the disposal of the EU and its member states, and by analysing how these instruments have been used concretely in configurations of areas of limited statehood and contested orders.

Based on this research, WP5 will be able to provide policy-relevant insights on how the EU can best foster resilience in the context of its Global Strategy and on how the rise of populist parties affect the external relations capacities of the EU.

Pol Morillas, Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (WP5)

The EU is not only suffering from the consequences of instability in its Southern and Eastern neighbourhoods but is also experiencing a decrease of its influence to shape developments on the ground, due to the combined effects of limited statehood and contested orders.

The EU Global Strategy reflects the changing security environment in the EU’s neighbourhood and embodies a growing feeling of being under threat. At the same time, it encourages the EU and its member states to take full advantage of the toolbox at their disposal to face these threats, fostering the resilience of their external action.

EU-LISTCO’s WP5 analyses the preparedness of the EU and its member states to anticipate, prevent, and respond to threats emanating from the conditions of limited statehood and contested orders and their deterioration into governance breakdown and violent conflict.

The research carried out aims to conceptualise what means for the EU to be prepared when facing these threats; to analyse the responses, strategies, and policy tools at the EU’s and its member states’ disposal; and to prepare the ground for policy recommendations on how to strengthen their preparedness. This work package also identifies the political conditions in the EU such as the rise of populism that are affecting the external action capacities of the EU.

Riccardo Alcaro, Istituto Affari Internazionali (WP6)

In a world of growing complexity, challenges including great power competition, regional fragmentation, and climate change—to name just a few—make knowledge exchange between scholars and practitioners a necessity.

EU-LISTCO’s WP6, led by the Istituto Affari Internazionali of Rome in cooperation with the Freie Universität Berlin, fosters such exchange in the area of limited statehood and contested orders, which it sees as default conditions in international politics with which the EU has to deal one way or another.

EU-LISTCO defines areas of limited statehood as areas in which the central government struggles to set and enforce rules and lacks full monopoly over the means of violence; and contested orders as areas in which local and external actors espouse and pursue competing views of how societies and political systems should be organized.

Areas of limited statehood and contested orders are consequently conceptualised as systemic risk factors, leading to the emergence of significant security threats whenever they deteriorate in governance breakdowns and/or violent conflict. EU-LISTCO assumes that limited statehood and contested orders create vulnerabilities to social cohesion, economic welfare, and political stability. WP6 aims to promote researchers-practitioners exchanges and contribute to defining, anticipating, and possibly preventing risk factors from turning into actual threats, as well as providing research-based policy advice to respond to such threats.

DATA SNAPSHOT |

||

This infographic, produced by the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB), highlights EU-LISTCO’s research goals, activities, and data about the project’s team. To enlarge the image, click here.

LATEST PUBLICATIONS |

||

Blog post

Status Stalemate In The Caucasus

Thomas de Waal

Moscow’s recognition of both Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states in 2008 has benefited no one—including the two territories and Russia itself.

RECENT EVENTS |

||

Conference

EU-LISTCO Kick-off Conference

Berlin

Organised by the Freie Universität Berlin, EU-LISTCO’s consortium partners engaged in discussions on the project’s work packages, agenda, and future empirical research.

Public Roundtable

Ring of Friends or Ring of Fire? Instability and Autocracy in the EU’s Neighbourhood

Berlin

Tanja A. Börzel, Ekkehard Brose, Hervé Delphin, Wolfgang Ischinger, Nathalie Tocci

The EU needs to prioritise in its foreign policy agenda to address most pertinent security challenges Europe is facing in its neighbourhood.

EU-LISTCO MEMBERS SAY |

||

“3 years, 14 institutions, 2 main questions: Under which conditions do areas of limited statehood & contested orders experience governance breakdown & violent conflict? How can the EU’s preparedness to anticipate, prevent and respond be strengthened? #EULISTCO @GPPi”

IN THE NEWS |

||

Politico Europe

How Europe Can Save the Iran Deal

Riccardo Alcaro and Nathalie Tocci

Europe has traditionally sought to maintain a strong transatlantic bond, while promoting of a variety of goals in its surrounding regions, beginning with the Middle East. But when it comes to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action reconciling these two objectives is regrettably no longer possible.

Eurasia Review

To Whom Does Crimea Belong?

Andreas Umland

The political circumstances of the 2014 Crimean referendum cast doubt on the claim that the Ukrainian region’s population had freely and almost unanimously voted to join Russia, as well as the historical justifications for Moscow’s land grab.

Institute for Human Sciences (IWM)

The “8s” in Czecho-Slovak 20th Century History as European Turning Points

Jacques Rupnik

On the 50th anniversary of the Prague Spring, the iconic moments in Czecho-Slovak history might help understand the critical junctures in Europe’s past and the current crises facing the continent.

PeaceLab Blog

Security Assistance and Reform: Bringing the Politics Back In

Philipp Rotmann

Security assistance and security sector reform are both about the allocation of power over the instruments of violence. External supporters can only succeed if they can integrate their projects into a broader strategy for political engagement with partner countries.